Bay Area II: CFAR Workshop

This is the second of two posts relating my Bay area visit of August-September 2016. You can read the first part here.

This is a very (6+ months late) belated write-up about my experience at the Summer 2016 Workshop for AI Researchers run by the Center for Applied Rationality (CFAR). To add insult to injury, I’m not even going to talk about the rationality techniques we studied! As a short summary though, the workshop content, the participants, and above all the CFAR people were all awesome, and I got a huge amount out of attending. The atmosphere throughout was electric and immensely fun. I’ll be writing more about quantified self & rationality practice over the coming months, as I get this blog up to speed.

The workshop was held from August 30 - September 5 at Ellen Kenna House, a beautiful Victorian mansion that sits on the top of a hill in Oakland, California. There were about ~30 participants and ~10 CFAR staff. The participants were AI researchers hailing from a variety of places: BAIR, SAIL, MIRI, FHI, IDSIA, Google Brain, MILA, were some of the labs/institutes represented.

I had 'Bino's album Because the Internet on loop the whole week. Apt or corny?

In this post I’m going to formulate two fun prediction/betting games that I learnt about at the workshop: Calibration Market and Bid/At.

Calibration Market

This is related to the game of the same name by Andrew Critch. I’ll formulate it somewhat formally here.

A calibration market \(M\) is a tuple \(\left(P,\tau,B,\right)\), where \(P\) is a proposition that is evaluated at some time \(\tau\). \(B\) is a finite sequence of bets \(b_0b_1b_2\dots\), where each bet \(b_i\in\(0,1)\) is interpreted as the subjective credence of a player that \(P\) evaluates to \(1\) at time \(\tau\). For obvious reasons, values of 0 and 1 are not permitted. The market is initialised with a prior \(b_0\), usually bet by the house or market maker, who may in turn participate in the market subsequently. Once \(P\) is evaluated, the market closes. Each bet (except the first) is scored by the log ratio with the previous bet

\[\begin{align} S[i] &= 100\log_2\left(\frac{b_i^P(1-b_i)^{1-P}}{b_{i-1}^P(1-b_{i-1})^{1-P}}\right) \\ &= 100\left[P\log_2\left(\frac{b_i}{b_{i-1}}\right) + (1-P)\log_2\left(\frac{1-b_i}{1-b_{i-1}}\right)\right] \end{align}\]Informally, you gain points if you move the market towards the truth, and lose points if you move it away from the truth. For each player \(p_j\), you add up the total score for the market.

Some other rules:

- You may not bet after yourself, and

- You may not alternate bets with someone else.*

* This second rule is deliberately left flexible and informal: how it is interpreted, and how strictly it is applied is down to taste.

The equation above is an example of a proper scoring rule: to maximize your expected score one should always bet your true beliefs – this was pointed out to me by Matthew Graves. Let your true belief be \(a\), and your bet be \(b\). Let the previous bet be \(c\), though we will see that it turns out the value of \(c\) doesn’t matter. Consider your \(a\)-expected score as a function of \(b\):

\[\mathbb{E}[S] = a\log_2\left(\frac{b}{c}\right) + (1-a)\log_2\left(\frac{1-b}{1-c}\right).\]We can maximize the expected value simply by setting the derivative to zero and solving for \(b\), since it is trivial to show that \(\mathbb{E}[S]\) is concave. The derivative is given by

\[\partial_b\mathbb{E}[S] = \frac{a-b}{b(1-b)},\]which naturally implies that one’s expected score is maximized if one bets one’s true beliefs:

\[\arg\max_{b}\mathbb{E}[S] = a.\]The animation below illustrates this, showing how the optimal bet changes as we sweep our belief over the interval \([0,1]\):

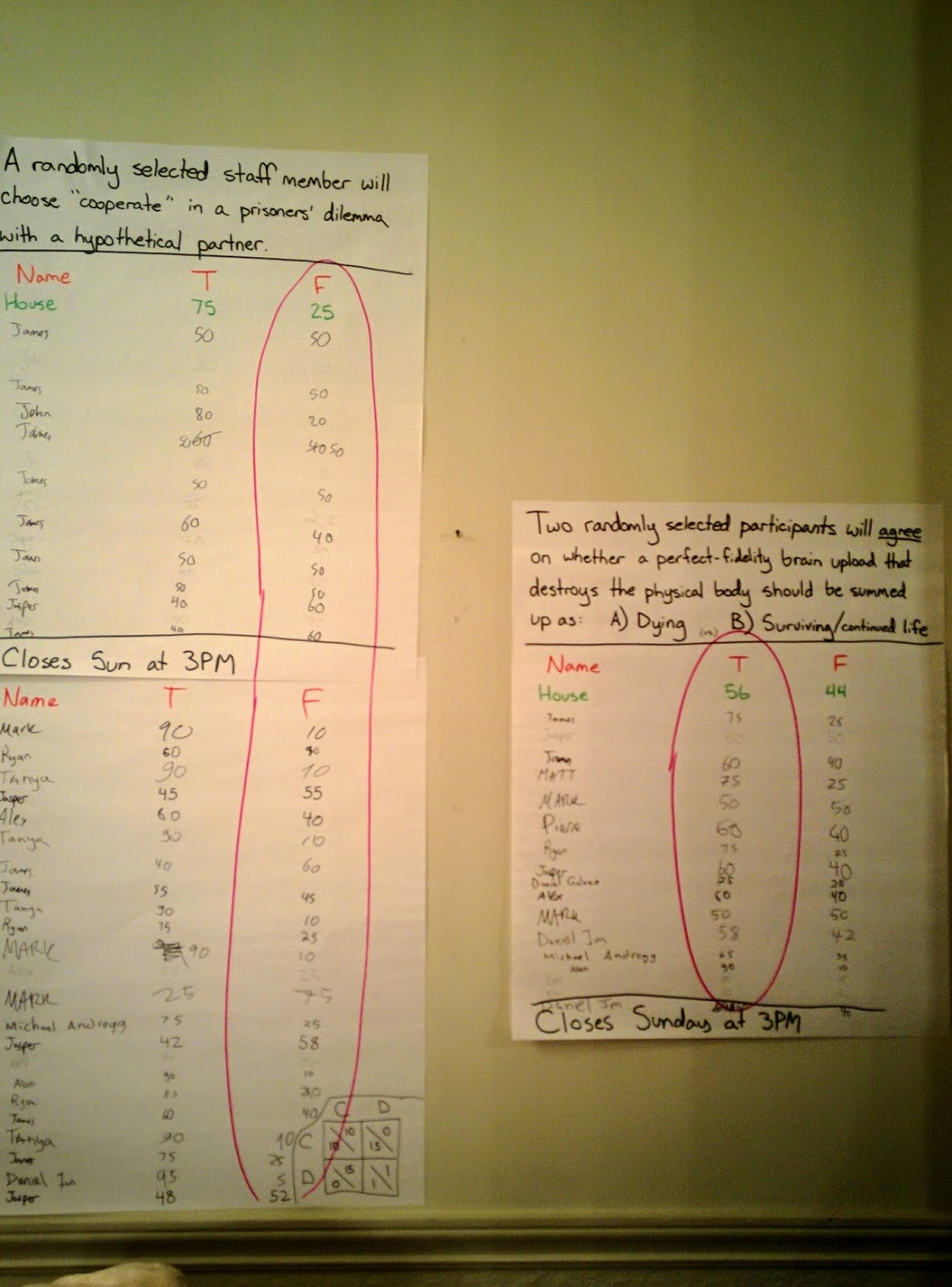

Of course, one of the central notions at CFAR is recursive: becoming more rational requires metacognition, i.e. reasoning about reasoning. For this reason, when we played the game, many of the propositions were self-referential in nature. This makes for much more interesting markets, and goes to the whole meta theme. Propositions were typically of the form of “a randomly selected participant will willingly do/say X when prompted”, or “the outcome of this market will be X”, rather than propositions of the form “it will/won’t rain tomorrow”. There were numerous calibration markets run throughout the week, and they added to the generally stimulating and fun environment.

Bid/At

I’m told that this game is played a lot at Jane Street. The game is simple: You make a market out of some future/unknown outcome \(Q\) that is quantifiable. For simplicity, let \(Q\) be a positive-valued random variable. The market consists of two or more players buying and selling contracts relating to the outcome \(Q\):

A contract between two players \(p_1\) and \(p_2\) is executed as follows: \(p_1\) pays \(p_2\) \(x>0\) credits, and receives in exchange a promise stipulating that after the value of \(Q\) is known, \(p_2\) will pay P1 \(Q\) credits. Information flows in the market by players sending price signals to each other: a player may bid a value \(x\) to indicate they are willing to buy a contract for \(x\) credits, or conversely declare they are at a value \(y\), which indicates they are willing to sell a contract for \(y\) credits.

In general one would bid \(x\) if one believes that \(\mathbb{E}[Q] > x\), and accept bids at \(x\) if one believes that \(\mathbb{E}[Q] < x\). Like the calibration game above, players can make inferences about the beliefs of other players (based on bid/at prices) and update their own beliefs; presumably the market converges to a fixed price under certain conditions, though I haven’t thought about it enough to write down what those conditions must be.

The main interesting game-theoretic difference between Bid/At and Calibration is that in Bid/At, you are incentivized to hide your subjective belief \(\mathbb{E}[Q]\), so as to potentially reap the biggest margins when buying/selling contracts. In any case, it’s a game that rewards forming accurate predictive models about the world, with an added element of risk management.

If played in earnest, the players would keep records of all contracts, and when \(Q\) is realized, the contracts are paid out at some (pre-determined) credits-to-dollars conversion rate.

Bonus: Group Decision Algorithm

Duncan told us about this algorithm in the context of coming to a decision about which restaurant to go to as a group of people. The algorithm is simple:

- Anyone can suggest one or more new options for consideration at any time.

- If only one option remains under consideration without veto, and no more options are suggested, then this option is chosen and that’s the final decision.

- If more than one option is under consideration sans veto, the final decision goes to a vote, using the usual procedure for redistributing preferences in the case of ties, breaking deadlocked ties at random.

- During the candidate selection process, anyone can veto an option at any time; this option is then immediately and permanently removed from consideration. The person that made the veto must then generate three new suggestions.

The algorithm is designed to completely obviate the situation in which someone suggests some option which gets immediately shot down/vetoed without any promising alternatives presented in its place. Once a first option is suggested, the algorithm is guaranteed to produce a decision that satisfies people’s preferences (assuming that people actually veto options they aren’t happy with), provided the set of feasible options isn’t exhausted; in the case of restaurants this certainly won’t happen, since everyone’s gotta eat eventually :). The multiplicative factor of three seems well-tuned to yield good results and fast convergence: it’s just enough to disincentivize flippant vetos, but small enough to not make vetoing too onerous (e.g. most people can easily suggest three new restaurants), so that everyone has a good chance of having their preferences satisfied.

There’s more interesting analysis to be done here (if it hasn’t been done already). Once I have the time to learn more about Bayesian markets, I’m sure there’ll be some interesting microeconomic/game-theoretic analysis of Bid/At. I’d also quite like to implement both Bid/At and Calibration as fun small-scale asynchronous multiplayer web app-based games. That would be an intereesting engineering project, and would be a pretty fun tool for the rationality community to practice on, to supplement things like PredictionBook. To be continued!